Views from outside atmosphere

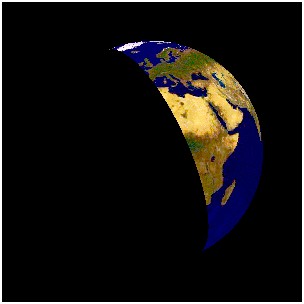

On the left is a preview image showing the texture map of the Earth's

surface and the orientation of the Sun's illumination. An image like this

can be computed very quickly, which is useful in setting-up interesting

views. The image is a 4° view of the Earth from 240,000 km above the

equator at longitude 0° and the Sun is over-head at latitude 23°N,

longitude 110°E. This corresponds to Midsummer in the northern hemisphere.

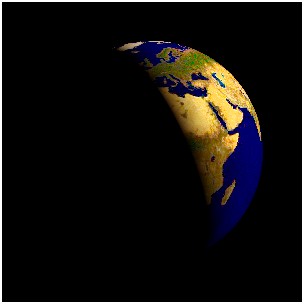

The image on the right shows how the Earth's surface looks when we ignore

scattering in the the atmosphere and only absorption is considered. Notice

the reddening around the North Polar ice cap resulting from long light

paths.

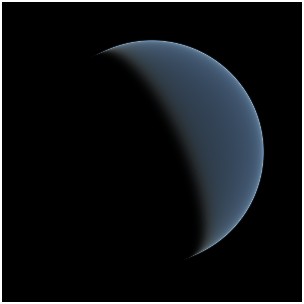

In the image on the left we see only the light scattered by the atmosphere itself. We can now clearly see the the effects of the Earth's shadow -- light is reaching parts of the atmosphere on the dark side of the Earth, beyond the terminator as indicated in the first image. Finally, in the right-hand image we consider all light scattering, absorption and reflection from the Earth's surface together. A full-size, full-colour, version of this image is available (161k).

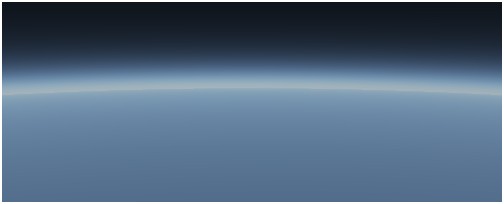

This a another view of the Earth and its atmosphere, again from 240,000 km above the surface. The view point is directly above 30°N, 90°W looking at a point on the surface at 55°N, 90°W. The Sun is overhead at 23°N, 90°E. A full-size, full-colour, version of this image is available (149k). |